5 Ways to Recognize and Prevent Dehydration While Hiking and Training

There are five important factors to address when you perform physical activity in the heat and humidity: dehydration, hydration, sweat, cooling off the body, and heat acclimatization. Ignoring any one of them can impede your performance during your hiking workout, backpacking trip, or trek. Understanding how to address these factors could be the difference between your next spectacular adventure and a bout of heat illness, such as heat exhaustion or heat stroke.

Let’s take an in-depth look at each of these to learn how to help the body stay properly hydrated and cool.

Dehydration Negatively Affects Your Hiking Workouts and Adventures

What is dehydration? Dehydration is the condition in which your body is lacking the levels of water to function properly. If you don’t intake sufficient levels of water for your body weight and for the outdoor temperatures, you may become dehydrated quickly. Dehydration is influenced by exercise intensity, environmental conditions such as temperature and humidity, and availability of fluids during exercise.

How can you tell if you are dehydrated?

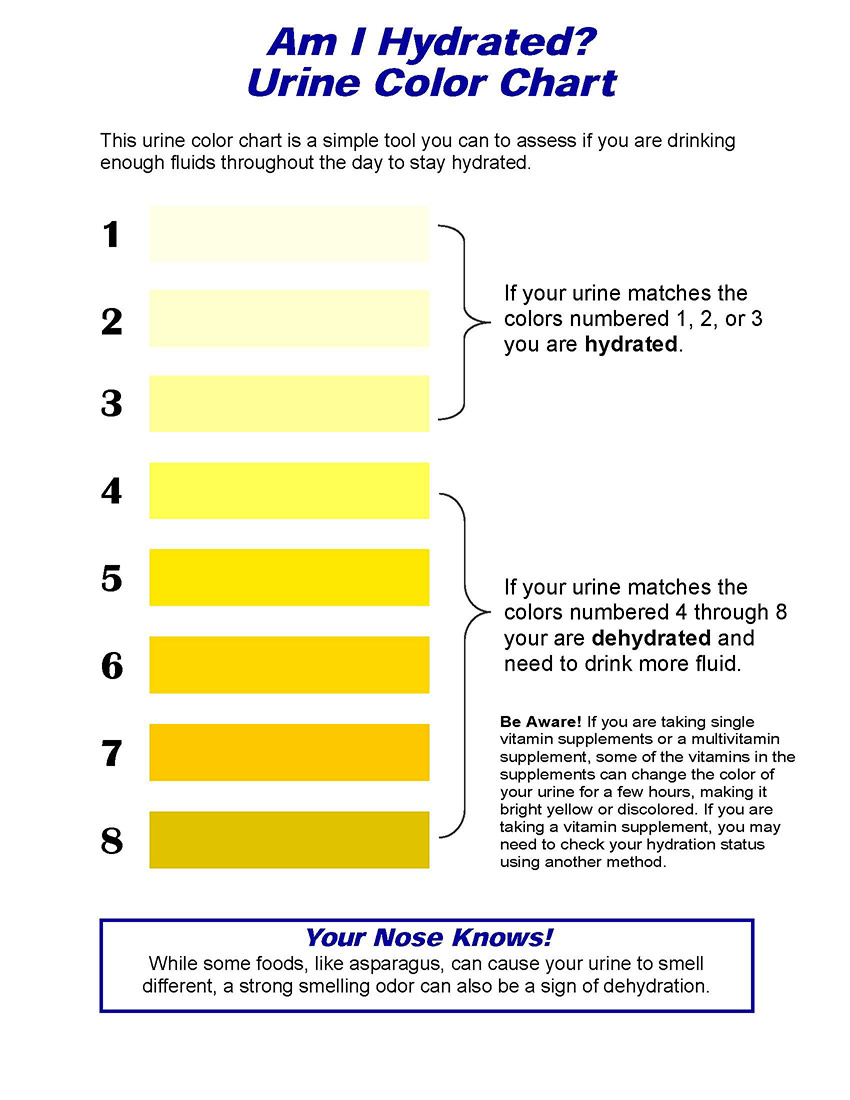

Your urine can be an indicator if you are dehydrated. If it’s colorless or light yellow, you’re well hydrated. If your urine is a dark yellow or amber color, you may be dehydrated. The following urine color chart is a way to assess your hydration status:

This a list of other effects or signs of dehydration:

- Little or no urine

- Urine that is darker than usual

- Dry mouth

- Sleepiness or fatigue

- Extreme thirst

- Headache

- Confusion

- Dizziness or light headedness

- No tears when crying

Do not use thirst to tell if you are dehydrated.

Research indicates that by the time we feel “thirsty” our body is 1-2% dehydrated. Evidence from the American College of Sports Medicine and National Athletic Trainer’s Association also suggests that relying solely on thirst as a means of replacing fluid losses during exercise, especially in hot environmental conditions, may prevent the full restoration of body water losses, leading to involuntary dehydration. This means thirst is not a good indicator of hydration needs, but rather that the body is already dehydrated. Individual fluid replacement plans should be calculated based on an individual’s weight and fluid loss during workouts.

What puts you at a higher risk of dehydration?

Some people are at higher risk of dehydration, including people who exercise at a high intensity (or in hot weather and high humidity) for too long, have certain medical conditions (kidney stones, bladder infection), are sick (fever, vomiting, diarrhea), are pregnant or breastfeeding, are trying to lose weight, or aren’t able to get enough fluids during the day. Older adults are also at higher risk. As you get older, your brain may not be able to sense dehydration. It doesn’t send signals for thirst, therefore pre- and post-workout weighing is vital for being aware of hydration rate and needs.

Understanding how caffeine can effect dehydration is important

Caffeinated beverages are known as diuretics and may increase the production of urine at rest but have not shown to do so during exercise. If you choose to drink caffeinated beverages, recommendations are to consume it up to every 30 minutes during exercise at a rate of 3 mg of caffeine per kilogram of body weight. Note that consuming levels higher than the daily recommendation will require greater intake of water to maintain fluid balance.

Hydration is critical to staying energetic and safe during your hikes and walks

Prevention of dehydration is better than having to fix dehydration

Did you know that water makes up more than half of your body weight? Your body depends on water to survive. Every cell, tissue, and organ in your body needs water to work properly. For example, your body uses water to maintain its temperature, remove waste, and lubricate your joints. You lose water each day when you go to the bathroom, when the weather is really hot, and when you’re physically active.

Hydration is defined as the process of replacing lost water in the body. We can calculate our bodies’ daily water intake need by dividing your body weight in pounds by two. The resulting number is the number of ounces of water you should drink per day. This number does not take into consideration your hydration rate based on physical activities; therefore, you can measure that by weighing pre- and post-workout. Use the following guidelines to calculate your additional hydration needs based on body mass losses:

- Before the workout or activity ensure you are well hydrated.

- Step on the scale pre-workout or hike and record your weight in pounds or kilograms.

- Step on the scale after your workout or hike and record your weight.

- Calculate the difference by subtracting the post-weight from the pre-weight.

- This number is the pounds/kilograms of weight loss during activity.

- Every 2.2 pounds lost is equivalent to 1 liter of fluids loss.

Note: Greater than 2% of body weight lost in a single exercise session increases risk of impaired physical performance and dehydration. Severe dehydration is considered greater than 5% body loss combined with dry mouth, extreme thirst, dizziness, dark urine, and confusion and should be treated by a licensed medical professional.

Fluid replacement during training and adventure

When considering fluid replacement for hiking, trekking, and outdoor adventures, you should take into account your daily intake, sweat rate, and gastrointestinal tolerance of consuming large fluid volume during exercise. For example, sweat rate can vary according to body size, environmental conditions, exercise intensity, acclimatization status, and other factors. Reliable estimates of sweat losses based on some of these variables exist; however, they are not valid for every person and should only be used as an estimate when specific calculations cannot be conducted.

Individual recommendations on fluid replacement should be based on individual data and not population estimates

In addition, competition goals and experience must be factored into fluid-intake decision planning. A 50-year-old participating in her first Grand Canyon rim-to-rim hike in one day who has a 0.4 L/h sweat rate and a goal of finishing in 12 hours should not receive the same hydration plan as a 28-year-old elite male hiker with a sweat rate greater than 2 L/h who is attempting a 7-hour finish time in the same hike.

According to the National Athletic Trainer’s Association, it is best for the physically active to restrict fluid loss to no more than 2% body mass

The reason for this is to help maintain the physiological, perceptual, and safety aspects of exercise while aiding in exercise recovery and subsequent training sessions. According to the latest research of fluid intake for exercising individuals, keeping body mass losses <2% also decreased risk of heat illness and dehydration. Fluid replacement is individualized and based on calculated body mass losses, urine color, and sweat rate. The goal is to maintain the best fluid balance possible before, during and after activity.

Which fluids hydrate the body?

Plain water is ideal for staying hydrated, but other drinks and food can help too, especially if you become dehydrated. Fruit and vegetable juices, milk, and herbal teas add to the amount of water you get each day. Electrolyte and hydration powders, tablets, and drinks can contribute positively to hydration as well due to their ability to replenish the sodium, sugars, and minerals lost during hikes and physical activity.

When do I need to replace fluids lost during activity to avoid dehydration?

Ideally, exercise-related body fluid losses should be replaced in a short time frame by water, and dietary intake should replace body fuels used during exercise with food and hydration formulas. Post-exercise body mass losses generally require replacement with 100% to 150% of calculated fluid losses due to increased production of urine, particularly when fluid recovery time is limited (i.e. less than 4 hours).

When recovery time is extended to more than 12 hours, balance is achieved with food and fluid consumption. Most individuals can avoid fluid-balance problems by drinking regularly during and after exercise and eating a healthy diet. In healthy individuals, the thirst mechanism is governed by a combination of the concentration of chemicals in the blood and water volume as the body attempts to maintain proper fluid balance. Thirst typically increases at about 2% dehydration and markedly decreases when rehydration restores this level. Competitive and recreational athletes who have chronic medical conditions should consult their personal physicians regarding hydration recommendations and strategies to avoid exacerbating their conditions.

Sweating is the primary mechanism the body uses to regulate its temperature

It occurs in the 4 million sweat glands located throughout our skin or dermis. Once signaled, sweat glands release water and tiny amounts of electrolytes such as potassium, sugars, and sodium through the pores. When the sweat hits the air, the air makes it evaporate by turning it from a liquid to a vapor. As the sweat evaporates off your skin, the body cools. The body will repeat this process as often as needed to regulate core body temperature. It’s important to understand that the body needs to be hydrated in order for the sweat mechanism to work at its full potential. This will allow for the internal body temperature to be regulated and reduces the risk of heat exhaustion and other heat illnesses.

The body is constantly working to maintain a balanced temperature despite the changing outdoor environment

The body works optimally when it remains at a temperature of about 98.6ºF (37ºC). If your body gets hotter than that, your brain doesn’t like it — it wants your body to stay cool and comfortable. So, the part of your brain that controls temperature – called the hypothalamus – sends a message to your body, telling it to sweat to try to lower body temperature. (Recall that when you sweat the heat transfers from your body to the sweat and the evaporation of sweat removes the heat). Although it is an excellent cooling system, if you’re sweating a lot on a hot day or after a long hike, you could be losing too much water through your skin. Then you need to put liquid back in your body by drinking plenty of water. In addition to water, you will most likely need to replace electrolytes among other nutrients.

What are electrolytes and why are they important in the fight against dehydration?

Electrolytes are minerals in the body that have electrical charge and are responsible for balancing water in the body. They also assist with moving nutrients into cells and moving wastes out of cells. Sodium, calcium, potassium, chloride, phosphate, and magnesium are all electrolytes. You get them from the foods you eat and the fluids you drink, therefore you can replenish them through hydration formulas and food intake. If a person is dehydrated, it is likely they will lose the much needed electrolytes while performing physical activity. This is often noticeable through the white line produced on our hat or forehead, or the salty taste of your sweat. These are literally the ‘salts’ our body needs to maintain body functions and regulatory balance.

Since the body relies heavily on water intake and excretion to achieve balance, sweating increases the bodies need for water and electrolytes

If your urine indicates you are dehydrated or you are thirsty (1-2% dehydration), it is important to replace with fluids that have electrolytes. Note: if your activity extends beyond 60 minutes, adding a hydration formula containing natural sugars is important so that your muscles and heart continue to function properly. Using a hydration formula that contains natural sugars is another consideration in order to replenish your glycogen stores for sustained energy and performance. Sodium is also important to replace: Evidence in research shows failure to sufficiently replace sodium losses will prevent the return to a hydrated state and stimulate excessive urine production.

Practical Ways to Battle Dehydration

Summer hiking and backpacking adventures require a lot of time in the sun that can make it difficult for the body to cool off. Here are some practical ways to stay cool while facing the summer heat:

- Check the weather forecast and try scheduling your hike or adventure for one of the cooler times of day. An early morning or late afternoon hike can make a big difference in avoiding the potentially dangerous heat. Typically, 11am-5pm are the hottest times of day and best to avoid for outdoor activity. Training during the hot times is necessary, however, if you are preparing for a hike, run, or any event that will take place during hot times of the day.

- Choose a trail or hike that includes several shaded areas along the way. This will allow your body time to recover from the heat and balance temperature regulation. It is also a great way to acclimatize when the heat of summer starts to increase.

- Don’t skimp on water. Pack more than you expect to drink. An adult can absorb approximately 1 liter of liquid per hour.

- Freeze your water bottle or keep it water cool longer by filling the bottle or bladder with at least 1/2 ice. This will provide you cooler liquids to ingest for a longer time period.

- Bring a hand towel and use it to wipe the sweat off of your body every 20-30 minutes. This will enhance the “cooling off” effects of the evaporating sweat.

- Avoid dark clothing as it draws more sun. Wear light colors instead that attract less heat, such as white or yellow.

- Choose quick drying breathable clothing to keep your skin cool and able to sweat properly. Fabrics that are light weight and breathable include synthetics such as polyester, nylon, and spandex.

- Consider using a breathable sun hat to provide extra shade for your neck and face while allowing your head to stay cool.

- Bring a change of shirt and/or socks. Being able to remove wet clothing halfway through a hike enables the sweat mechanism to continue to work efficiently. Wet clothing inhibits the evaporation of sweat that leads to cooling effects.

- Take rest breaks in shaded areas if possible. A 1-5 minute break in the shade can allow the body to cool down, refresh, and give you time to replenish with food and drink.

Acclimatizing and Humid vs. Dry Heat

A hot or humid environment can affect sweat rate, sweat onset, sweat electrolyte concentrations, heart rate, rate of perceived exertion, and internal body temperature changes

The cooling of human body, in hot environments, is achieved not by sweating but by the evaporation of sweat. In very humid conditions, although we can sweat heavily, we may not feel ”cool” because the increased moisture in the air makes it more difficult for sweat to evaporate. When sweat cannot evaporate, heat has difficulty dissipating from the body during exercise, difficult hiking conditions, etc. Instead, sweat simply drips off the body, which doesn’t cool us off very well.

In this environment, it is helpful to carry a towel to regularly wipe off the sweat. It can also be helpful to bring an extra set of clothes and change them if they become soaked with sweat. Because humidity deters evaporation of sweat, you will desire a breeze or a fan. Heat is trapped in the sweat and the breeze helps the sweat evaporate.

In climates with dry heat, sweat generally evaporates without wetting the skin surface by the heat supplied on the surface of the skin known as insensible evaporation. Because the heat is unable to move from the skin to the quickly evaporated sweat, the cooling effect is not achieved, and the body temperature rises steeply.

Acclimatization can help you tolerate difficult environments that are hot and humid

In cases in which there is even a little wind blowing, it can help in evaporation of sweat in a hot and humid climate. But, when the evaporative cooling in a given climate is not optimal, it can be better tolerated by athletes and hikers that are used to that climate: this is known as acclimatization. Acclimatization is adaptation to the environment, which is achieved with proper training over a lengthy period of time.

The higher temperature of the surrounding environment does not ensure that the sweat will always evaporate. The sweat may start dripping off a person who is not used to the hot climate and the body heat transmission through evaporation becomes ineffective. On the other hand, if the same person gets used to the same hot climate, he will look drier and feel cooler due to evaporative cooling. To reiterate the point, acclimating means getting used to the climate.

To avoid overheating and dehydration in dry heat, you should slowly adapt to the heat by gradually increasing exposures to the heat in small increments of 20-30 minutes.

To avoid excessive body fluid loss and dehydration in a humid environment, you should use a towel to wipe off the sweat. This will dry the skin and allow the body to cool off and continue to re-sweat to regulate temperature.

When enjoying the great outdoors this summer, it is important to understand how to adapt (acclimate) to training and hiking in the heat of the day

If there is not enough time to acclimate or you are hiking in an environment that you have not acclimated to, then incorporate hydration and other strategies detailed above. Hot and humid weather can sneak up on us, but by following the tips for staying cool, checking your urine, measuring hydration rate and staying hydrated with the proper amounts of fluid your body will have what it needs to beat the heat.

Ready to take your adventure training to the next level? Contact us now to set up your free fitness consultation.

References:

Adams, W. M., Vandermark, L. W., Belval, L. N., & Casa, D. J. (2019). The Utility of Thirst as a Measure of Hydration Status Following Exercise-Induced Dehydration. Nutrients, 11(11), 2689. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu11112689

Casa D.J., Stearns R.L., Lopez R.M., Ganio M.S., McDermott B.P., Yeargin S.W., Yamamoto L.M., Mazerolle S.M., Roti M.W., Armstrong L.E., et al. Influence of Hydration on Physiological Function and Performance During Trail Running in the Heat. J. Athl. Train. 2010;45:147–156. doi: 10.4085/1062-6050-45.2.147.

Shibasaki M, Wilson TE, Crandall CG. Neural control and mechanisms of eccrine sweating during heat stress and exercise. J Appl Physiol. 2006;100(5):1692-701.

Disclaimer: Exercise is not without its risks and this or any other exercise program may result in injury and/or death. Any person who undertakes these exercises does so at their own risk. To reduce the risk of injury you should consult your doctor before beginning this or any other exercise program. As with any exercise program, if at any point during your workout you believe conditions to be unsafe or begin to feel faint or dizzy, have physical discomfort, or pain, you should stop immediately and consult a physician. It is important to perform exercises properly to avoid injury, it is recommended that you acquire help and teaching in order to undergo any new exercise program safely.